From Print to Pitchfork: Why We’re Here

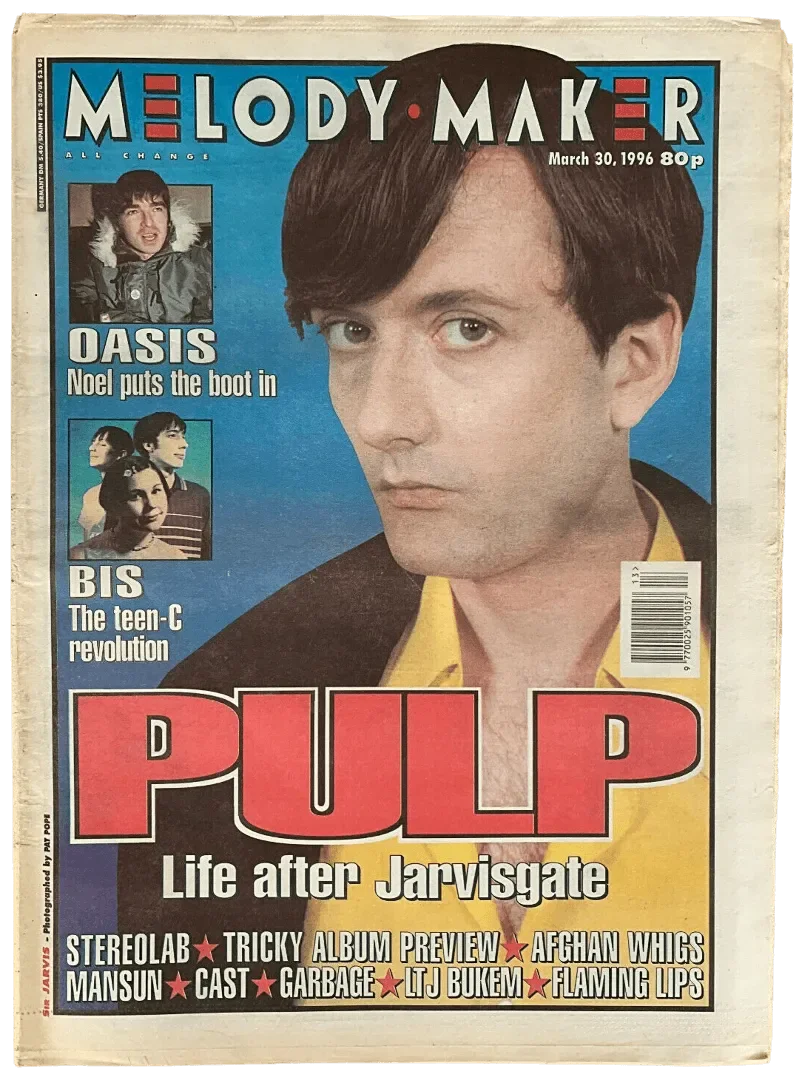

Music fans used to rely on magazines. NME and Melody Maker offered in-depth interviews, thoughtful reviews, and curated recommendations that were a formative education for teenagers, and landing on the cover could launch a band’s career.

Fans developed a deep trust in the taste and integrity of such outlets, with a clear editorial voice and a passion for music that emanated from every page. You could spend hours immersed in a single issue learning about genres, scenes, and influential artists that came before for just a few pounds.

These print outlets built up promising newcomers, and their mission was as much to support artists as to inform their audience. An NME cover was one of the top goals for a rising band, and the press was an ally to musicians, amplifying their music to the wider world, working tirelessly to find exciting new music and share it. Journalists were key players in the ecosystem, with fans depending on magazines to discover their next favourite bands, and artists relying on them to reach listeners.

As music consumption moved online, so too did music journalism. Founded as an indie music webzine in 1996, Pitchfork started small but rapidly gained traction in the early 2000s with its daily updates. Suddenly, fans didn’t have to wait a week or a month as reviews and news were updated in real time on the web.

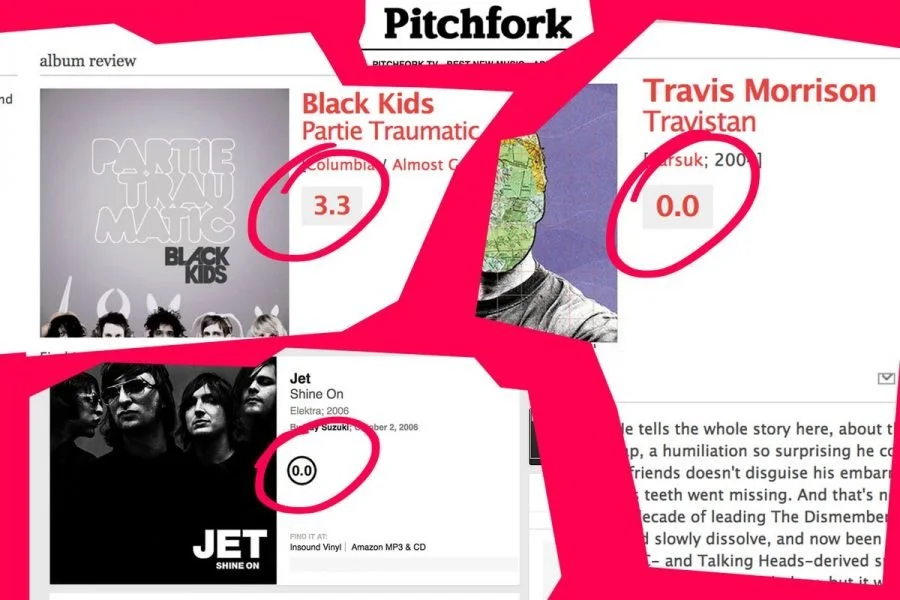

Niche genres and unsigned bands that mainstream magazines ignored could now find coverage on blogs, but the online format also changed the tone of music journalism. Reviews were sometimes harshly comic in their negativity, with Pitchfork becoming notorious for its snarky takedowns, such as a 2002 review of an album by Jet that didn’t even use words, just a video of a chimpanzee pissing in its own mouth. Extreme negative opinions translated into attention-grabbing traffic, as a scathing pan would get shared and build their notoriety. Pitchfork’s decimal-point rating system seems calculated to start fights, and an albums score could make or break an album’s reputation in an instant.

Metacritic further quantified the reviews from Pitchfork and other sites into simple averages, turning music critique into a pure numbers game, whilst print outlets tried to adapt by putting more content online. The landscape had shifted.

As the 2010s progressed, the internet’s influence on tone and incentives in music journalism became impossible, as outrage and provocation drove engagement. Negative posts get disproportionally shared, and music sites weren’t immune to this dynamic with many leaning into sensationalism, over-the-top snark, and clickbaity headlines to chase precious pageviews. A brutally hilarious pan could go viral in ways a nuanced, measured critique never could in an unpleasant race to the bottom, as the sheer volume of content exploded. The barrier to entry for music criticism had dropped to zero, and any fan could publish their opinion with a tweet, Facebook post, or YouTube reaction video. For any major album, one could find hundreds of amateur reviews and reactions online within days, eroding the authority that publications like Pitchfork or NME once held.

A popular meme of the era was “let people enjoy things” and a writer who panned a hugely popular artist could expect to be swarmed with online abuse, doxxing, and death threats from enraged fanbases, and by the late 2010s, professional criticism had become noticeably softer as publications learnt there was little upside to a scathing review of a pop release if it would only bring social media backlash. An analysis in 2018 showed that over 80% of albums on Metacritic scored 70 or higher, and Pitchfork hasn’t doled out a perfect 0.0 bomb in years. Ironically, the pendulum swing to positivity is just another symptom of the internet’s impact.

On one hand, the web incentivised ruthless snark and hyperbole, and on the other it empowered fans to mob critics who they thought went too far. This upheaval has failed emerging artists. In the old model, the music press acted as a crucial intermediary between new artists and the public. Curious readers would seek out a young bands music after a glowing review of their brilliant debut album, whereas now the major sites that remain focus on artists who already generate clicks because of industry hype. The industry has grown complacent about promoting new artists, who have been told to take on the burden of promotion themselves.

It’s no longer enough for a musician to write great songs and play great shows. They’re now expected to be full-time social media content creators, churning out TikToks and Instagram reels to build their brand. Record labels and managers will push artists to maintain a constant online presence, outsourcing marketing work that the music press would have helped with in the past. Forcing artists to be online influencers obviously distracts from the actual music when they devote so much energy to self-promotion.

This is an indictment of what music journalism has become. Should musicians feel like they have to shout on social platforms to be heard? Don’t we miss the kind of carefully curated recommendations that old-school mags used to excel at? Should new artists be spending more time as marketers than musicians? Isn’t marketing fundamentally at odds with the creative process?

In chasing clicks on the Internet, the music press has lost its trust and purpose. The shallow clickbait, mean-spirited pile-ons, and neglect of emerging artists stem from that breakneck transition to digital media, but those of us who grew up thumbing through thick pages feel a pang of nostalgia. We remember when music journalism felt like a passionate conversation, not a cacophony of hot take algorithm content.

Something needs to change and we need an antidote. Even as traditional publications dwindle, the desire among fans hasn’t disappeared. Let’s take the best of the past and infuse it into a new format that learns from these mistakes.

Artists shouldn’t have to be influencers.

At Sherwood, we post one brilliant album every few days, chosen because it deserves your attention. Every review is essentially a love letter to a great album. We aim to be a bridge between hungry listeners and new artists. Welcome to our small corner of the internet. Go click on the Discover page and see what you find.